For my long-awaited return to Scandinavia, centered on visiting a dear Norwegian friend of many decades, I decided to catch up with the modern trends in art, architecture and urban planning while in Oslo, Norway.

What struck me initially in Oslo is the civility – the thoughtfulness and efficiency of transportation and other public amenities, welcoming tourist conveniences and functional, contemporary urban design. It’s a city made for walking and accessibility; sidewalks are wide, drivers and pedestrians follow streetlights and ramps and elevators are built into the architecture, not merely add-ons. People speak English quite easily, and during summer travel you hear languages from everywhere, so it’s easy to navigate.

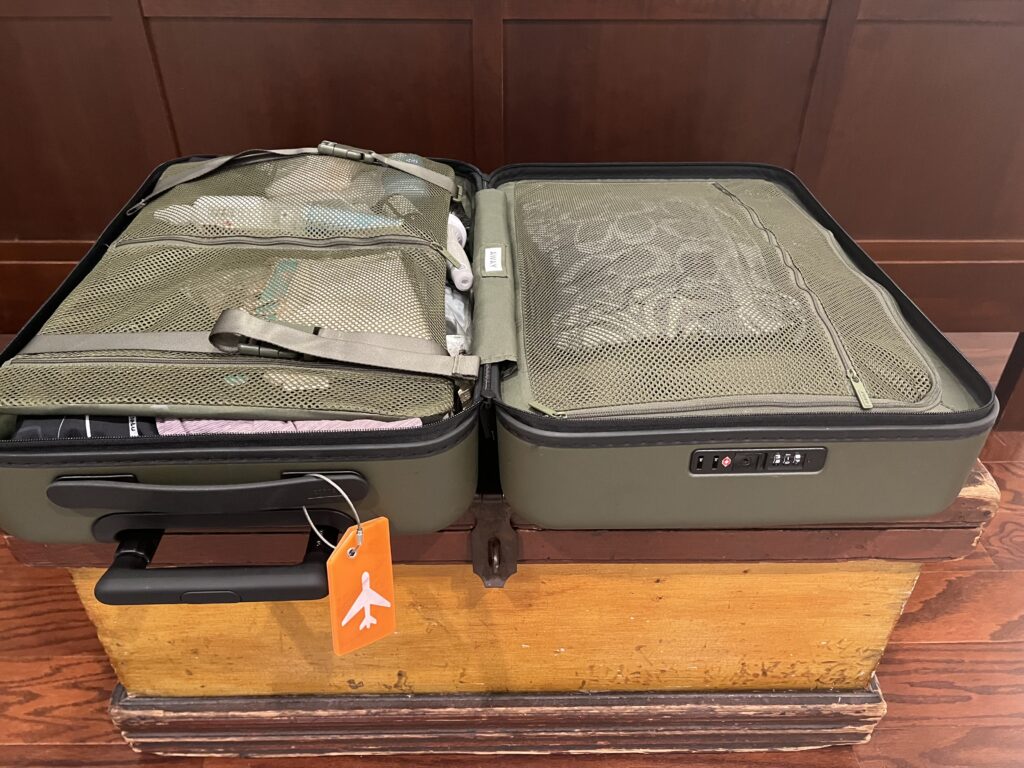

With carryon only for my overseas journey (a la Rick Steeves), I exited the airport and met my friend Bjorg outside; we walked a short distance to a very modern light rail train and a 20-minute ride to her suburb of Stabekk just west of central Oslo.

Although environmentally conscious, Norwegians need cars outside the cities largely because of the terrain. Superhighways take years to build, a slow process of boring through mountains and shaping flat terrain along the curving coast. Yet, there are many incentives, including convenience and price, to use local trains and buses or ride bikes, regular to battery powered electric bikes, which my friends use for trips to the grocery or a ride up to the suburban hills for hiking or skiing. Traffic is frequently managed by roundabouts, and there is little honking or impatience among drivers.

In short, Norwegians are rightfully recognized for their civic pride and mutual respect. With 5 million people, sturdy patriotism and social democracy, the tax system makes possible free public education (starting with preschool), free health care and a retirement pension program as common benefits for all. There are pressures on the system, however. Immigration is drawing people for service jobs and education, creating competition for the benefits. And, the discovery of oil in the late 1960s has led to more revenue for the social welfare benefits (oil profits are taxed heavily by the government to be invested in the Norwegian people), yet also social stratification (for example, the emergence of private schools in some communities and options for private medicine for those who can afford it). Still, the overall norms and standards of community responsibility have stood firm.

I’ve learned that 2.5 weeks is generally my limit when I’m traveling solo and changing locations; for this particular get-together, I calculated 3-4 days on my own, each in Oslo and Copenhagen, wrapping around a week-plus excursion to my friend’s summer retreat on a small island off Norway’s southeast coast.

Exploring Oslo’s Art and Architecture

Today’s compact Oslo, accessible on foot, train and bus and city bikes and e-scooters, sets aside limited parking to discourage cars. On previous visits, I’d toured thoroughly into Viking history and frontier culture, including the singular “stave” carved wooden churches and Viking museums. Instead, on this trip, in three days, I focused on urban Oslo, with districts illustrating its evolving industrial heritage, and on selected outdoor spaces and parks featuring traditional arts and culture in western Oslo.

Oslo Sentrum (the central city) has a large train station connecting visitors from all directions. Walking from there, you will see several quais along Oslofjord, each with its own architectural personality and cultural destinations. Along the landscape to the left is Akersus Festning, a medieval fortress jutting out into the water, and to the right along Karl Johans Gate, charming parks landmarks such as the National Theatre and eventually the current Royal Palace. Rather than these sights, which I’d seen in previous visits, I chose the newer areas that are part of the city’s three-decades-long transformation:

Aker Brygge & Tjuvholmen – Oslo’s “inner harbor” area is a district of former industrial wharves and shipping piers converted into stylish restaurants, bars, shops, art galleries, museums and modern apartment buildings. There are a few small city beaches with public swimming along the fjord and floating saunas (offering refreshing ice baths in winter, cooling dips in summer and steaming saunas year-round). Parks are filled with sculpture and ample kid-friendly playgrounds amid benches and flower gardens.

- We started at the contemporary National Museum, which opened in 2022, a dignified yet dramatically understated building that embraces classic and modern art and design. While predominantly Norwegian, the museum incorporates selected international masterpieces grouped chronologically in a well-organized fashion that facilitates a self-guided tour. Labels describe the art in Norwegian and English. The museum is large (86 rooms on two floors, plus other art in open spaces) and we were selective – focusing on Norwegian artists. Painter Edvard Munch, whose comprehensive Munch Museum is nearby, has an entire room with representative signature work, including a vibrant version of his international favorite, “The Scream.” There are significant paintings by Harald Sohlberg, a neoromantic whose “Winter Night in the Mountains” (1914) is one of his most famous studies of breathtaking topography and a majestic snow-covered moonlit landscape. In the same room, “Hell,” an 1897 sculpture by one of Norway’s most prolific artists, Gustav Vigeland, is graphically descriptive and horrifying. (For more about Vigeland Park in northwest Oslo, see below.)

From there we strolled along the quai to Tjuvholmen Sjømagasinet restaurant for a leisurely outdoor lunch along a canal for delicious seafood specialties. My fish soup, based on a light cream fish stock, was loaded with tasty bites of mussels, cod and salmon. Across the aisle two women were working through a large plate of crab and lobster claws.

After lunch we walked through the Tjuvholmen Sculpture Garden along the fjord to the Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, outside an architectural gem in its own right and inside, a cavernous space showcasing one of Europe’s most comprehensive collections of contemporary international works, from sketches to multi-media. On the way back to the train, we passed rows of stylish apartment buildings, lined with cafes and restaurants along the sidewalk, and the King’s Yacht docked just across the channel.

Bjorvika – A newer district with some of the most imaginative apartment and office building designs, Bjorvika reshapes a former container port along the downtown’s eastern side; it winds around another series of quais centered on the waterfront Oslo Opera House (home to opera and ballet). The Oslo-based architectural firm Snøhetta (known for other remarkable spaces such as the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) created this building rising from the quay that you can climb up to and along its roof – and which is a must-do, regardless of what else appeals in Oslo. I haven’t had such a fascinating climbing experience since working my way up to the Acropolis in Athens two years ago!

Constructed of 36,000 blocks of white Italian Carrara marble, the opera’s exterior slopes and steps allow people of all abilities, including those in wheelchairs and children on scooters, to reach the top and take in the spectacular view of the city. Behind it is the towering new Munch Museum. Because of the light rain, I decided to take the long length of stairs, rather than potentially slick marble slopes, to the bottom. Inside the tall glass walls, wavy oak paneling created warmth and coziness.

On my list across the canal was SALT, a funky warren of brightly painted pyramid shaped wooden structures and food stands that becomes a lively entertainment venue at night. I took a 10-minute detour to walk through it briefly, past more floating saunas (and a notable number of swimmers taking a quick dip in the 60-degree water). Having studied much about Munch in previous trips, I passed on the stunning Munch Museum but walked around it to see more of evolving Bjorvika, including its futurist housing development, Barcode, a series of individual buildings completed in 2016 and seemingly blending into one organic form.

For lunch, I stepped in out of the rain across the street from the Oslo Opera House into Oslo’s main library, the Deichman Bjorvika, a striking six-story cantilevered structure whose first floor is an animated community center, with creative “maker spaces” for children and adults, a small shop and Centropa restaurant. With moules frites and a small bottle of sparkling water, I enjoyed another delicious lunch, listened (lightly) to the French couple at the table behind me and watched people ascending and descending along the Opera House roof.

Frogner Park and Vigeland Sculpture Park – Up in the hills of western Oslo sprawling homes of the affluent and the embassy district command the vistas, within walking district of Frogner Park, once a large manor estate and gardens, and Vigeland park, the world’s largest sculpture garden dedicated to one artist. His 214 sculptures stretch from bronzes along a bridge over a pond to large granite figures on two hills. In sum, each a masterpiece in its own right, they expressively, yet simply, depict all of life, from infancy to death. I’ve been to Vigeland before, and each visit brings new insights into human emotion through the stonemasons’ bold yet sensitive strokes. Perhaps the best-known section of the park is the tall “Monolith” a colossal rock 17 meters high and weighing 280 tons, which was blasted from the central region of Norway’s stone industry and shipped by boat to Oslo. After 13 years of work, it is wrapped in a labyrinth of intertwined figures. This granite column is surrounded by 36 clusters of figures speaking to all forms of love (from tenderness and joy to sadness and rejection). I could have spent hours studying each one.

Baerum’s Verk – This enclave in the hills above Oslo is a collection of more than 40 shops, galleries and eateries, a living village created from the smelting huts and laborer’s modest houses dating back to the early 1600s; later Baerum’s Verk became a major foundry dedicated to ironworks from nails to cannonballs to wood-burning stoves you still see today in farmhouses, mountain cabins and newer homes in Norway. Recreated with modern versions of the crafts, like Colonial Williamsburg, the village welcomes visitors to relive some of the history and view artisans, such as glassblowers, woodcrafters, knitters and bakers who are continuing the artisan traditions in contemporary forms. The rain-soaked river once propelling the foundry today had become a mammoth waterfall, while stunning sculptures populated the parks and picnic areas.