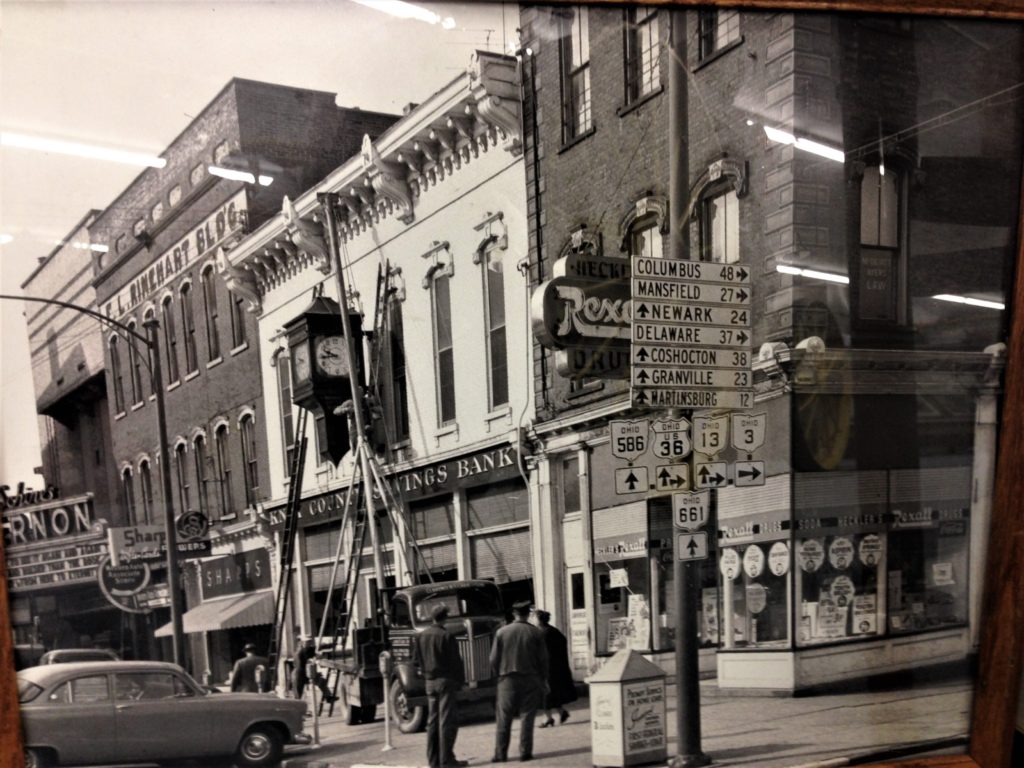

When it comes to small towns, there’s not much difference in Nebraska and Ohio, or probably most other states. Watching Alexander Payne’s award-winning film, Nebraska, brought that home. Though set in the Plains, the scenes in fictional Hawthorne, Nebraska (the real town is Plainview) reminded me of Mount Vernon in central Ohio, the subject of my father’s watercolors of the 1950s, and of his own hometown of New London about 60 miles north. Each of these towns is designed on a similar template – the equivalent of Main Street extends three to four blocks from the center.

The power of the film lies in the vast black and white landscape, the flat tableau of farms stretching to infinity in all directions. Relationships are less by dialogue than the often wordless connections between people, with insights arriving through observation and intuition. “Flatness” is a metaphor for revealing hidden truths. A friend from California who’d visited Columbus, Ohio, recently said he was quite struck by the flat landscape that offered brilliant sunsets all the way to the horizon, instead of being obscured midway by mountains. I’d always taken that for granted.

In an interview with NPR’s Terry Gross, the film writer said that “flatness” was also about the people. I grew up that way – being emotional is not highly valued. People are “flat” and that’s ok.

I completely related to the scene in which cousins, aunts and uncles sit around the living room and exchange two-word sentences. The setting reminded me of Sundays at our grandparents. No razzle-dazzle, just people talking, sharing what’s on their minds, with snippets forming conversational threads punctuated by comfortable silence.

“Like many writers and filmmakers, at least earlier in your career, you want to explore the mystery of the place you’re from – those early buttons, how it haunts you,” director Alexander Payne said of his home state of Nebraska in a New Yorker interview (Oct. 28, 2013). Payne was born and raised in Omaha and still spends part of the year there, the rest in LA.

It must be the season for hometown reminiscences, because writer Jim Harrison reflected in a travel article in today’s New York Times about how growing up in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula left its imprint on his life and fiction. “…There’s nothing like returning to a farm with horses and chickens, and then on to a fairly remote cabin off a two-track road where when you try to sleep at night you hear a river flowing, probably the best sound on earth,” he wrote.

Like them, what I learned about my father when writing The Artist’s Eye and about the world through his eyes while he painted carved an indelible imprint in my consciousness, values and the way I “see.” And years later, that still-evolving understanding continues to take sharper form.