Remembering Robbie Robertson, songwriter, guitarist and best known as a member of The Band, who died Aug. 9, after an extraordinary career. This article is republished from 2016.

Testimony, the memoir by The Band’s guitarist and principal songwriter Robbie Robertson, ends with The Last Waltz, the group’s final concert in 1976 and often called “the end of an era” for the melange of rock, blues and folk that fueled the ’60s and ’70s. Forever etched in memory as the pulsating, doe-eyed virtuoso guitarist in the magenta scarf that iconic evening, which was captured on film by Martin Scorsese, Robbie Robertson drew several hundred aging rockers and younger people to Dominican University in Marin County just 25 miles north of San Francisco’s Winterland, where the The Last Waltz was performed.

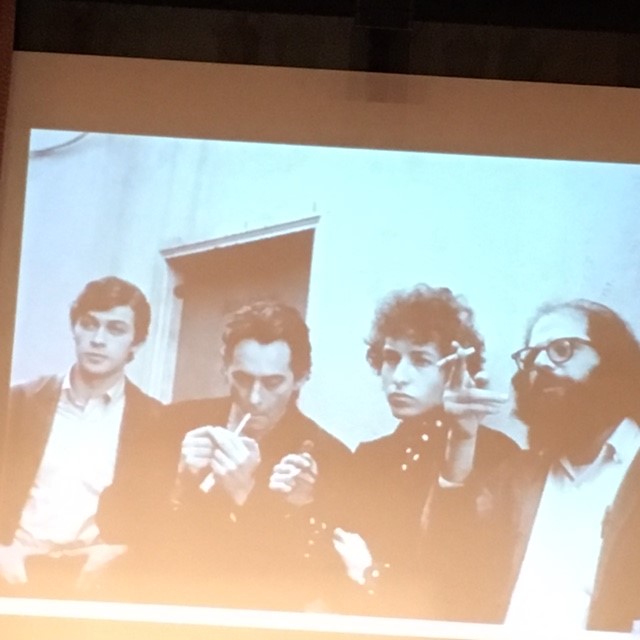

A handful in the audience tonight had been at Winterland that extraordinary evening, when The Band honored the traditions of rockabilly, gospel, blues, rock, folk and other strains that became their recognizable style; in celebration, they performed with other major music influencers – musicians like Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, Van Morrison, Mavis Staples, Muddy Waters, Eric Clapton and Bob Dylan – and strikingly Dylan had such a good time that he smiled the entire time. Testimony was a celebration of their youth.

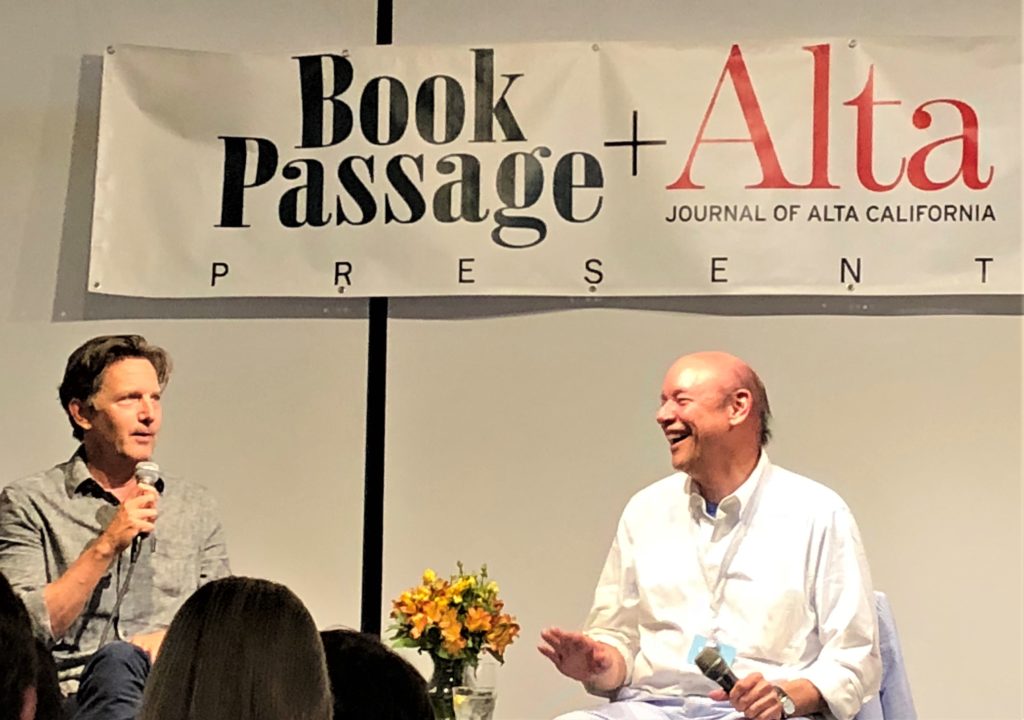

“Forty years ago this week,” Robertson said at the Leadership Lecture Series co-sponsored with Marin County’s and San Francisco’s amazing independent bookstore Book Passage. “That must be a mistake – was it, maybe, really 20 years ago?”

He spoke for most of us! Our gang back in Washington, DC, saw the film when it was released; we rarely skipped concerts back then, and despite many lifetimes since, still watch The Last Waltz on available new media formats. Winterland is no more, The Band is no more (only Robertson and Garth Hudson are still alive) and most of its fans are old enough to be their grandparents, even if they don’t feel they are. We can all agree that we’ve changed while Robertson remains a colorful, absorbing storyteller, his measured verbal pacing providing richly detailed anecdotes with humor, irony, reflection, generosity, poignancy and – as ever – passion.

A size or two up from his slimmer youth, Robertson doesn’t have the deep wizened lines of a Mick Jagger, and shares happily rather than typical wistful reflections about “back then.” His stories reveal insights and observations that seem as freshly drawn as his original experiences. He remains a craftsman, striving to get the story right with the same authenticity that has placed him among the best guitarists of all time.

“Sixteen years on the road, the numbers scare you,” Robertson mused in the film at age 33. “Twenty years on the road? I couldn’t discuss it.” Yet, 40 years later, he is still making music and his 494-page book is called “one of the best books on rock and roll ever written” by Rolling Stone founder Jann Wenner. Other reviewers agree. (Clearly Robertson, 73, has more to say – the book stops when he was 33.)

“There’s been so much written about that era – a lot of it is garbage. I know, I was there!” he remarked during the evening with Dan Stone, founder and editor of Radio Silence, a magazine about literature and rock & roll. When Robertson hooked up with Ronnie Hawkins and the others who would leave Hawkins and become The Band, “I knew it was something fresh.” He calls Levon Helm “my big brother…he made me want to play better.” He also recalled when he played with Bob Dylan the first time at Forest Hills in New York: the audience booed and threw objects at them because Dylan had introduced electric guitars rather than sticking to his acoustic core. But pioneering Dylan told his musical associates, “‘the world is wrong and we’re doing something special,'” Robertson recalled. “So we went out and played faster, harder. Throughout the national tour, audiences kept throwing things, but they were wrong.” The Band and Dylan had a long association and this year Dylan’s vision was sealed by the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Today only two of the five Band “brothers” remain, Robertson and Garth Hudson, whose paths cross on occasion. Heart disease, cancer and suicide took the others. In his book, Robertson talks honestly and movingly about the heavy drug use that was a key factor in their breakup.

Back in the mid-1980s, I had the occasion to meet Danko, Helm and Manuel backstage when they were trying to resurrect The Band in a new form and I was a journalist in Philly. We bumped into them in the hallway and they invited us up to their “green room” for a beer. They were friendly and funny, having a heck of a time and willing to share it without any pretense. Shortly after, Manuel committed suicide. It was terribly eerie to have just been in a conversation with him.

A few years later, I interviewed Robbie for the Philadelphia Inquirer while he continued to write new music and I was writing a book on creativity.

“There were so many influences in our lives,” he told me reflectively then, “and you mix all these influences in this big pot and actually invent a new kind of gumbo. The Band invented something. We stuck some things together, and not completely dissimilar to the beginning of rock and roll when there was this tremendous blues and gospel influence…And it had character. There were voices of characters in the songs. It was just a completely new flavor….We just did what we did and didn’t understand it. And through that kind of innocence and the fact that we’d been together for a while, we were pretty good at what we did…We were rebelling against the rebellion without even knowing about it.”

I asked him what he told his then-teenage son about life in the music biz. “It’s worth it,” he said. “If it’s that strong a passion – if you feel, ‘I have to do this to breathe.’ On the other hand, if it’s like, ‘I want to do this to be rich and be a star,’ you won’t get the depth out of it that is worthwhile…But if it is really following your bliss, then do it…This wasn’t casual for me…You can’t do your work because of the bonuses that come with. You have to do your work because you love this more than anything else in the world, you need to do this to live your life, to breathe. It’s all about passion…”